The Royal Collection Trust has an extensive collection of photos of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. After doing quite a bit of experimentation and study on Cennini’s Il Libro dell’Arte, it was really cool to see these drawings and pick out the different methods used with an eye toward the process and materials used. While not contemporaries, I’ve picked out some of these drawings to discuss how they relate to Il Libro dell’Arte. I highly suggest browsing the website and looking at the wide variety of drawings in various states of completion, various techniques, and various subjects. For each of these I have included a hyperlink to the drawing on the Royal Collection Trust’s website in the heading and an explanation underneath.

*Note!* Because of the death of the Duke of Edinburgh, the links do not seem to be working correctly. If you have a problem getting to the drawing, copy the name of the drawing, copy into the search bar on the website, and add da vinci to find the drawing I’m referencing.

Head of Leda

17.7 cm (7.0 in) x 14.7 cm (5.8 in)

This drawing is worked in black chalk with pen and ink. Da Vinci made several drawings of this title, all that I found were of pen and ink and many had chalk for shading.

Design for an equestrian monument

14.8 cm (5.8 in) x 18.5 cm (7.3 in)

This is a rather preliminary sketch on blue prepared paper with a metalpoint. The collection of da Vinci drawings contain quite a few on colored prepared paper. The two most common colors seem to be blue and an orange.

Diagrams of a machine and tools for mixing mortar

22.4 cm (8.8 in) x 16.8 cm (6.6 in)

This is another sketch on blue prepared paper, but the blue is much more pale. The topic of the drawing is interesting because it is not an artistic stetch, but more of a practical drawing. Since this is a drawing meant to outline a process as opposed to an draft of an artistic drawing, the drawing is much rougher with less detail. For this drawing, da Vinci started with metalpoint and then inked in the design.

Head and shoulders of a woman

16.5 cm (6.5 in) x 12.4 cm (4.9 in)

This is another metalpoint drawing on light blue prepared paper. The face has nice definition and shading, while the rest of the drawing is very rough. The museum believes that the rough sketch was made by da Vinci and the shading was done by a student to practice.

The hindquarters of a horse

19.5 cm (7.7) x 12.7 (5)

I thought this drawing was interesting because it is part of an animal with great muscle detail. The color for the prepared paper is different in this drawing: a light pink. I got a very similar color with a little vermillion in the bone ash and white pigment.

A Map of Imola

44 cm (17.3 in) x 60.2 cm (23.7)

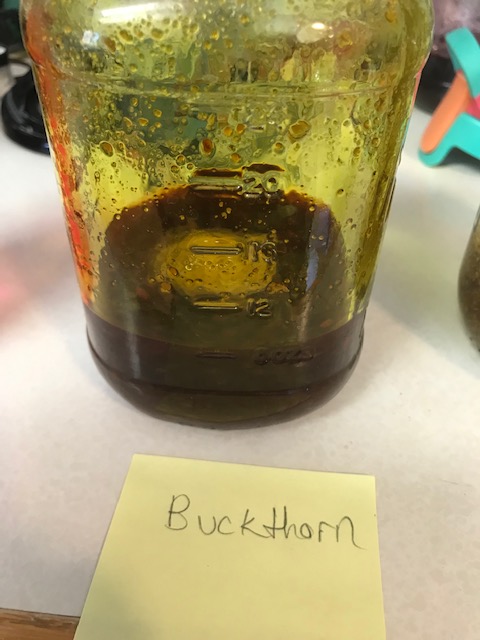

This drawing has some fun additions from just black chalk lines. The map has multiple colored washes to denote water and land features. The blue looks to be indigo. The yellow could be buckthorn due to the orange tint. Cennini said that drawings could be colored with washes of ink, pigment, or clothlets.

The head of the Madonna

24.4 cm (9.6 in) x 18.7 cm (7.4 in)

This is a drawing of the Madonna worked with red and black chalks on prepared paper. The interesting parts of this drawing when studying the drawing techniques listed by Cennini is the brush and ink shading and the white highlights. In chapter 10, Cennini talks about shading with ink diluted in water. He advocated starting with a few drops of ink in a walnutshell of water and then adding more ink to make darker shadow. You can see the ink shadow in the Madonna’s veil. Highlights were made with a little lead white in the Madonna’s veil.

The drapery of the Madonna’s arm

8.6 cm (3.4 in) x 17.0 cm (6.7 in)

There is a whole lot going on in this drawing. The drawing was made with pen and ink, perhaps over a silverpoint sketch since the paper is prepared with an orange tint. Red and black chalks add layers and depth while white lead wash adds highlights. This drawing was apparently used as a teaching tool since the hand seems to be done by a student.

Sprigs of oak and dyer’s greenweed

18.8 cm (7.4 in) x 15.4 cm (6.1 in)

I adore da Vinci’s botanical drawings. Many of his botanical drawings are done in red and white chalk on red prepared paper. This drawing has some holes along one margin which may indicate that it was bound into a notebook at one time.

Sketches of two standing figures and one kneeling figure

2.3 cm (.9 in) x 3 cm (1.2 in)

This is just a rough sketch in pen and ink on a scrap of paper, but I love that it isn’t beautiful. It isn’t perfect. It’s rough and makes me think of da Vinci’s process and how ideas and art evolve.